Whether you’re working through your first season of running or have lived in the running world for years now, you’ve likely had this thought pop into your mind at some point:

How do I run faster?

It’s a valid question, especially since running is one of those sports where you can constantly improve. But even with thousands of resources out there, it can still be tricky to find a coherent answer on how to actually achieve that increased running speed.

And that’s the frustrating part — there isn’t one foolproof method to get there.

Most resources will suggest pretty general “solutions,” like allowing more time for recovery, increasing your mileage more gradually, or alternating between different sports for a more varied workout. Don’t get us wrong; these are solid suggestions for your training, regardless of your performance goals.

But that’s what makes them ineffective for faster running: they’re way too general and aren’t targeted enough to achieve a goal as specific as increased speed.

The reality is that increasing your speed boils down to optimizing your biomechanics, power, and form, all of which might sound general, but are chock full of nuance.

So let’s dig into the nitty gritty and get you on track to speedier running, shall we?

Factors that Contribute to Running Speed

Although running is a natural and seemingly simple movement, it’s much more complicated than what you see on the surface. There are countless factors to keep in mind for optimal performance, and many of these contribute to whether or not you’re able to actually increase your speed.

Learning how to run faster is dependent on how you train your body — it demands an understanding of how to maximize energy and power while also requiring proper functionality of your skeletal and muscular structures.

This is where speed training and proper form coincide. Changing your running form can be a difficult process, but it’s far from impossible (and quite necessary for optimal running). When it comes to speed specifically, you’ll want to focus on the following key factors:

- Hip extension

- Power per step

- Time spent in float

- Cadence

- “Power Leaks”

If any of these terms sound foreign to you, don’t worry; by the end of this blog, you’ll have a stronger understanding of what each factor is, why it affects your running speed, and how to incorporate it into your training.

Factor #1: Increased Hip Extension

Let’s start out with a simple one.

Hip extension is just like running: it’s a natural, everyday motion that doesn’t require much thought, but it comes with unexpectedly complex biomechanics that have a big impact on efficient functionality and movement.

Any time you move your thigh away from the front of your pelvis (i.e., when you stand up or move your leg behind you), you’re extending your hip.

The biggest issue with this motion is that most people don’t practice it on a daily basis, at least not enough to actually benefit your muscles. After all, a majority of the population sits for most of their day, so it’s extremely common for people to develop tight hip flexors and a limited range of motion for hip extension.

But, aside from those unappealing words like “tight” and “limited,” what exactly does hip extension have to do with faster running?

Hip Extension and Power Generation

Believe it or not, inadequate hip extension means you’re limiting how much power you generate with every step (and the less power you have, the slower you are).

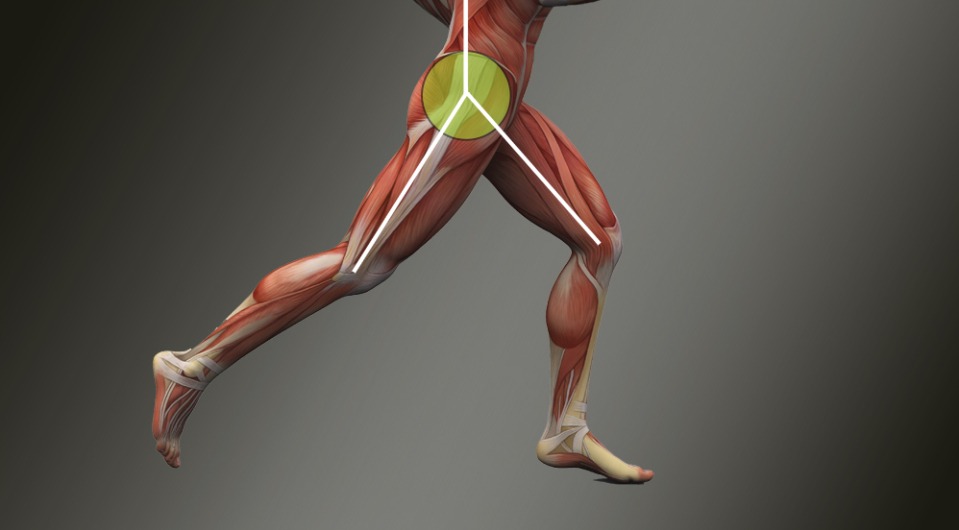

Here’s the basic idea: your hips are a part of a larger movement known as triple extension. If you aren’t already familiar with the term, triple extension refers to the point in your stride where the three main joints of your leg — the hip, knee, and ankle — are fully extended (at least, they’re supposed to be). And this simultaneous extension is actually the primary source of power generation for your running.

In order to generate the most power, though, your joints have to be capable of full extension, particularly your hip joint. As you’re running, you gain energy from contracting the gluteus maximus and extending the hip, and this energy is then transferred through the major muscle groups of your legs for a stronger push-off into your next step. Plus, some of that power gets transferred into your hip flexor muscles, which also contributes to a stronger and more energy efficient forward swing in your legs.

So don’t neglect that hip extension; even if your glutes are strong and activated, the muscle contraction alone won’t generate maximum power without full extension.

Hip Extension and Stride Length

On top of all this, having limited hip extension also means your strides will decrease in length, ultimately meaning that you’re spending more energy to cover less ground per step.

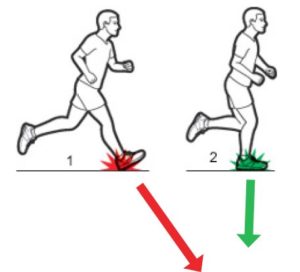

This is where many runners get confused — when experts suggest that a runner increase the length of their stride, the natural inclination is to reach their leg out farther in front of them. Unfortunately, this results in a common running form error known as over-stride (when your foot hits the ground in front of your center of mass), which increases the braking forces on your joints and increases the likelihood of pain and injury.

So, instead of extending your stride forwards, do just the opposite: focus on extending your leg further behind you during push-off. This allows you to lengthen your stride without over-striding.

But this takes us back to our Factor #1; if you don’t have enough hip range, you won’t be capable of fully extending your leg behind you. Not only will this prevent you from generating more power, but it’ll also limit the efficiency of every step through a shorter stride length.

How to Improve Hip Extension

Lo and behold, the best way to improve your hip extension is to increase how often you do it (which, yes, means more than just standing). Tight hip flexors and quadriceps are often the culprit for other joints and muscles to overcompensate for biomechanical deficiencies. So it’s particularly important that these muscles are nice and pliable to optimize your stride length.

Both your hip flexors and quadriceps respond extremely well to prolonged stretching. This means stretching the tissue for around 1-2 minutes, instead of the usual 30 seconds. With longer stretches, your muscles will have more time to deform and relax (basically becoming less stiff) and allow for greater overall movement.

The other key to sufficient stretching is consistency. To observe a true change in your hip range of motion, you can’t simply stretch for a few minutes every Saturday. In order to yield greater movement gains, you’ll want to practice these prolonged stretches 5-7 days a week.

However, before you get to stretching, make sure you know the distinction between stretching your hip flexors versus your quadriceps. There are a variety of ways to stretch your quads, but hip flexors typically require you to “tuck in your tummy” to get a stretch. If you want some inspiration for a solid hip flexor stretch, you can find plenty of detail for it here.

Factor #2: Maximized Power Per Step

What’s important to remember about running is that it’s a super repetitive sport; it’s built up of the same motions, cycled over and over… and over.

To put things into perspective, runners tend to hit about 2,000 steps for every mile they run — meaning any changes you make for one step will apply to literal thousands of steps. And if you were to increase how much power you generated for every step you took, you can just imagine how much total power you’d be putting into your performance.

Here’s the thing, though: when you’re analyzing the effect of power on running speed, it’s not just based on how much strength you have. It also involves how efficiently you can generate that power, and how well your muscles can absorb energy for effective contraction.

And that’s where the science comes in: to propel yourself forward with maximum efficiency and power, you’ll need an understanding of how your body absorbs shock and transfers energy for the ultimate push-off in every step. So let’s get to it.

Understanding Shock Absorption

Because of the repetitive impacts of running, it’s particularly important that your muscles and tissues are capable of properly absorbing shock.

Not only is shock absorption good for the health of your joints and tendons, but it also plays a vital role in maximizing energy sources for faster, more powerful running.

When performed correctly, shock absorption will prevent impact forces from adding stress on your joints and instead use the shock of impact as energy for more efficient muscle contraction during triple extension. This will ultimately allow for better power transfer and a more efficient stride.

You can even think about it this way: imagine each footstep is a bouncy ball. Whenever the ball hits the ground, the impact forces relaunch it back into the air by absorbing and reusing the shock as energy. But if the ball is deflated (or if your muscles aren’t activated or strong enough), it’s less capable of absorbing the energy and won’t bounce as high.

So don’t skimp out on the necessary work that keeps your muscles ready to absorb and reuse those bursts of energy.

Generating Forward Propulsion

On top of maximizing energy from impact forces, you’ll also want to work on how well your muscles can propel you forward.

If you’re wondering what that means, it all comes back to that handy triple extension.

As mentioned previously, full triple extension requires multiple muscle groups to contract. Theoretically, when this happens, this contraction will initiate a power transfer for energy to travel through your legs, starting at the hip all the way through to your foot.

Efficient power transfer will result in optimal push-off for every step, meaning you’ll maximize the amount of energy driving you forward. As a result, you’ll be able to travel more efficiently and cover more distance with every step.

Pretty neat, right?

How to Maximize Power Per Step

Here’s the part you were waiting for.

Power generation can be improved in a multitude of ways. Let’s start with muscular strength and explosiveness first. Powerful triple extension requires work from the main large muscle groups of your legs: your glutes, quads, and calves. Fortunately for you, you’re not limited in what kinds of exercises you do as long as they emphasize muscle strength and activation.

For example, helpful glute activation drills include isometric holds, monster walks, and squats with a band. For calf-strengthening, something as simple as calf raises can develop and maintain the strength needed for that final push-off. As for your quads, classic strengthening exercises like squats or lunges are often adequate. Most runners don’t need to deliberately focus on quad strength; you’re much more likely to experience weaker glutes or calves, so keep those exercises as a top priority in your training plans.

Once you’ve developed a solid baseline strength, you can switch your focus to building explosiveness. Developing explosive muscle power is typically done via plyometric exercises (commonly referred to as plyos). Plyometrics are meant to get your muscles more familiar with regular contraction and power absorption. Additionally, plyos help your muscles develop the proper response to the repetitiveness of running (it’s really just jumping from leg to leg, if you think about it).

Practicing double- or single-leg jumping activities will yield the best results for running, as these exercises train your muscles to build power every time you push off from the ground. As you’re practicing these jumps, it’s best to stand in front of a mirror so you can observe how you land. The key is to ensure that you’re not landing with any hip drop and that neither your knees nor your ankles overpronate (when they cave or rotate inwards). Make sure you’re meticulous about your landing form, otherwise it could throw off the shock absorption throughout your leg muscles.

Once your muscles are more accustomed to absorbing and reusing energy, you’ll be well on your way to having a more powerful stride. Remember: the key to efficient power is to keep your muscles in tip-top shape so they do most of the work.

Factor #3: Increased Time Spent in Float

As you run, there’s no point during your running gait where both your feet are on the ground — but there is a brief period of time where both your feet are off the ground.

These moments are aptly called the “float” phase of your running gait.

Typically, the faster you run, you’ll naturally spend more time suspended in the air, which is a result of generating enough power with every push-off. So, logically, by increasing the amount of time you spend in float, you’ll ultimately increase your speed, right?

Well, sort of, but there’s a bit of fine print to read.

How Float Time Impacts Running Speed

It might seem strange that you’ll become faster by spending more time in the air, since humans aren’t exactly made for hovering. But here’s the gist:

The more time you spend on the ground, the more friction you generate while running, and the more forces you have to slow down your forward motion. So, spending the least amount of time on the ground will go a long way in maintaining your speed.

You can think of it this way — the difference between mountain bike tires and road bike tires is all about the friction. Because mountain tires are much thicker and have very apparent treads, they’re built for creating traction against rocky mountain terrain (because no one wants to go flying off of those trails). Road bike tires, on the other hand, are much thinner and smoother to ensure the least amount of friction possible and make cycling more efficient.

Granted, for road biking, that isn’t so you can spend time in float, but it certainly helps with allowing you to travel at significantly faster speeds compared to using a mountain bike on the road.

Ideally, runners will spend more than 60% of their time in float — meaning that more than half of the time, you’ll be passively travelling forward. This doesn’t mean that you have to decrease how often you make contact with the ground (as you’ll read in the next major section); instead, you’ll want to improve the quickness, power, and efficiency of your strides to minimize the time your foot spends on the ground.

How to Increase Time Spent in Float

Here’s the best part, though: increasing your float time is as simple as following the advice from the other sections of this blog.

Talk about efficiency, right?

By increasing your hip range of motion, developing explosiveness, and improving your muscular activation, strength, and power, you will create performance boosts that transfer to an improved running economy and increased float time.

Factor #4: Increased Cadence

On the topic of improving your stride, it’s also important to optimize your running cadence (for more than one reason). Although your speed is affected by a myriad of factors, it’s extremely dependent on how long and how frequent your strides are — which is exactly what you can focus on with cadence training.

Cadence Improves Form and Generates Power

If you’re not already familiar with the term, your cadence is the number of steps you take every minute (each footfall counts as one). And typically, the higher your cadence, the faster and more efficient your running performance.

Which kind of seems like a no-brainer; after all — the more steps you take, the more ground you can cover in the same period of time, so it’d make sense that it’d make you faster, right?

Well, there’s more to it than just cranking out more footfalls.

Like most of these methods, increasing your cadence is ultimately more fuel-efficient. The more steps you take, the shorter your strides become, allowing your feet to land underneath you rather than in front of your hips (which keeps your feet closer to your center of gravity, therefore optimizing your shock absorption and efficiency).

Plus, increasing your cadence will cause your feet to touch the ground more often. Now, this only works well if you’ve optimized the power of your steps, as these additional points of contact will maximize how often you can propel yourself forward. (That being said, you still want to embrace the power of float, so make sure you’re working on those plyos to get your feet off the ground as quickly and powerfully as possible!)

How to Increase Cadence

Now here’s one of the best parts: increasing your cadence isn’t difficult to do (although these changes won’t — and shouldn’t — happen overnight).

Before anything, you’ll first want to start out by calculating your base cadence, which is an easy enough process. Run at a comfortable pace for a few minutes, then start counting those steps. Typically, the easiest way to do it without losing count is to choose one foot and count how many steps you take within 30 seconds; then, multiple that by two (to account for your other foot), and multiply that by two again (to get the total steps for a full minute).

Of course, you could also take the easier route and use some basic tech, too. Most smartwatches have the capability to record cadence now, so that’s a nifty alternative for anyone who isn’t big on counting while running.

Once you’ve got your current cadence, all you really have to do is gradually increase how many steps you take until you’ve hit your cadence goal. Many experts will suggest a weekly increase anywhere between 5-10% of your initial cadence, though that can still be a large jump. Increasing cadence 2-4 steps per minute each week gives your body plenty of time to adapt.

All that being said, you have a fair share of options on how to implement cadence training: you can focus solely on step count, use a metronome or songs with a set BPM, or train on a treadmill with a specific speed. Whichever method you choose is ultimately up to you — just be sure that you aren’t increasing your steps too much, too soon, and you’ll be well on your way to safely increasing your cadence.

Factor #5: Power Leaks and Inefficiencies

Alright, there’s been a lot of information to process already, but here’s the final chunk of details for achieving optimal speed (and it’s a big one).

Double-check your running form.

Yes, we mean ALL parts of your running form.

In addition to all the topics discussed above, you want to be sure you’re constantly assessing your running form and addressing any biomechanical deficiencies. Which is much easier said than done, and will likely require input and knowledge from a running expert… but at least we can give you a headstart on catching (and fixing) common running form errors.

Common Running Form Errors

If you’ve spent any time looking into proper form (which you probably have, since you’re here), you already know that focusing on your “running form” encapsulates a wide range of issues.

It’s impossible to cover all the potential errors in one subsection of one article, so we’re going to focus on errors that can impact your efficiency and speed.

For example, you now know how tight hip flexors can have a huge impact on your form. Not only can they limit your stride length and triple extension, but they’ll also impact your energy levels, thus decreasing your overall speed. Plus, with less muscle activation and decreased triple extension, your muscles aren’t capable of properly absorbing shock.

Similarly, you’ll want to pay attention to how your steps are landing. This alone can introduce a variety of biomechanical errors, but two of the most common issues are known as overpronation and over-stride.

Overpronation occurs when your ankles cave inward while you run, which only worsens your body’s ability to absorb shock (think back to that proper landing form for double- and single-leg exercises).

Over-stride is when your foot lands too far out in front of you (typically beyond your center of gravity), and it’s often a result of having a low cadence. If you over-stride, your bones end up taking the landing shock, rather than your muscles. Not only does this leave you vulnerable to increased injury risk, but it also means that all that potential energy from the landing shock can’t be utilized. So, make sure your feet are landing the right way and in the right place to avoid wasting energy (and increasing your risk of injury).

Also watch out for high vertical oscillation (or the amount of up and down motion while you’re running). The more your body’s moving up and down, the more energy your body’s spending for that vertical movement. That may not sound particularly detrimental, but any energy spent on something other than forward motion is basically a waste of energy that would have otherwise been used for additional power.

Plus, be sure to frequently check your running posture and arm swing. If you start feeling tiredness or tension in the middle of your run, take a second — shake out your hands, arms, and shoulders and get them feeling relaxed. Granted, tension alone isn’t a primary source of wasted energy, but it can occur super easily and only worsens your body’s fatigue the more it builds up.

Now, we know that these few errors are already a lot to pay attention to while you’re running, and in all actuality, many of them are hard to see or feel on your own to begin with. Most of the time, these errors are hardly even visible to the naked eye (especially during the real-time speed of running). This is where working with a running-specific physical therapist or an expert trained in biomechanics can help you thoroughly evaluate your form and identify any potential power leaks.

Final Thoughts

Huzzah — you’ve made it through this BEAST of a blog.

As you can tell, increasing your speed isn’t some one-and-done process; it takes in-depth knowledge, diligence, and patience to properly adjust your form and leverage your biomechanics for optimal running speed.

But it’s certainly an attainable goal, and you’re already on the right track after having tackled this onslaught of information.

So what are you waiting for? Get to training — your speed won’t increase itself!