Although running may seem simple in theory, it’s a surprisingly complex sport to nail down. Optimal running performance boils down to pretty specific biomechanics, and it’s surprisingly common for running deficiencies to cause damage to your body. Up to 79% of runners have sustained some kind of injury, whether it be a light ankle sprain or more long-term injuries like a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

ACL injuries in particular can be a grueling injury for runners — and it’s unfortunately been a growing concern over the past 30 years. There are approximately 100,000 to 200,000 cases of ACL ruptures in a given year, and a majority of these people require ACL reconstruction surgery in order to effectively (and safely) return to athletic activities.

Because ACL rehabilitation is an extensive process, most people are required to seek physical therapy to ensure proper recovery. In particular, physical therapy is focused on the athlete regaining ample range of motion and muscle strength, both of which are important for performing an array of sports and daily activities.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves — let’s address the elephant in the room.

When Can You Run After ACL Surgery?

After dealing with the pains of ACL injury and reconstructive surgery, it can be frustrating to hold back on your usual training. And although many athletes acknowledge the importance of erring on the side of caution, it’s natural to feel antsy about getting back to physical activity.

So the obvious question becomes: when is it safe to run again?

Well, surgeons will typically tell their patients that three months is enough time to recover before running again. If you’ve had an ACL reconstruction in the past, you were probably given that same time frame.

And maybe three months doesn’t sound too bad — but is it actually true?

Technically, yes. And by that, we mean very technically.

In most cases, three months is just enough time for the structure of the ACL graft to have healed enough to withstand forces of running. Now, that’s all well and good; but that’s the bare minimum of the healing process.

While the ACL graft itself can handle your running, it’s not the only important thing to keep in mind. There are other aspects of the rehabilitation process that require more attention (and time) to ensure they don’t impair your ability to run or put you at greater risk of reinjury.

So let’s review the rehabilitation process in a bit more detail to better understand how it works and what proper progressions look like.

Rehabilitation Protocol After ACL Reconstruction

ACL progression has multiple phases to work through, and each phase has its own checklist of tasks. Each of these checklists have to be completed before you progress into the next phase, which makes for a tedious (but thorough) process.

On the plus side, even if it’s tedious, it’s at least pretty straightforward, right? Finish off some checklists, and you’ll be back to safe running — plus, we’ll even walk you through it all.

Phase 1: Improving Your Movement

When it comes to rehab after ACL reconstruction, it’s important to start your first phase within 3-4 days after your surgery.

Maybe that sounds pretty ambitious, but it’s for good reason.

This first phase is all about easing back into regular leg movement post-surgery. Since this is the first of multiple phases, it’s important to start soon after reconstruction — if you don’t get to moving right away, your joints and tissues will turn stiff pretty quickly. Plus, waiting longer to work your muscles only means that you’ll have more ground to make up for during rehabilitation. So, to avoid these extra delays, make sure to get started soon after surgery.

You’ll first start out by reducing post-operative swelling, which is meant to help alleviate most of your post-surgical pain. Additionally, it will allow for greater mobility in your knee and increase the muscle capacity around your knee joint to help it move properly again.

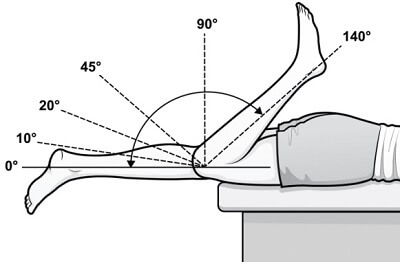

As a result, you’ll be able to work your way up to the other critical rehabilitation tasks, like restoring full range of motion in your knee. Being able to fully extend and flex your knee (when you straighten or bend your leg) are both super important aspects to restoring proper movement.

Having full range of motion is critical for when you begin restoring the activation and control of different leg muscle groups, like your quadriceps, hamstrings, and gluteal muscles. Full knee extension is particularly important for being able to contract your quadricep muscles, which allows for regaining quadricep muscle strength and providing stability in the knee for proper walking form.

You’re also going to start learning how to walk again throughout this first phase — and we don’t just mean getting back on your feet. More specifically, you’re going to re-learn proper walking mechanics to ensure that your ACL isn’t at risk of additional strain or reinjury. Here, it’s especially important that your knee is capable of full flexion, as it’s an important function of many essential daily activities. For example, simple activities like walking, putting on your shoes or socks, getting up from a chair, or going up and down the stairs all require bending at the knee. Plus, having increased flexion in your knee will also help you prepare for strengthening exercises in the upcoming phase of your rehab.

Not so bad, right? This whole first phase allows you to jump right into rehabilitative care without rushing the recovery process, and it at least gets you back to the basics of your day-to-day.

But, of course, it doesn’t stop there…

Phase 2: Restoring Your Strength and Control

Now that you’ve checked off all the tasks from phase 1 (and double-checked everything to make sure you really did them all), you can transition into the second phase.

The second phase will usually start somewhere between 4-6 weeks after surgery, but the time frame can vary — technically, it only starts after you’ve completed all the previous work from the first phase.

Once you hit Phase 2, this is where you start to improve the strength and balance in your surgical leg. In particular, the strength goal for this phase is to regain 80-90% of strength based on the current strength of your healthy leg.

Restoring the strength and control of your leg is critical for your progression into ballistic (or impact) activities like running and jumping — your muscles have to be strong enough to handle all the loading forces of your activity, which can be up to 3 times your body weight. If you aren’t able to adequately strengthen the muscles around your knees, hips, and ankles, you’ll be prone to reinjury if your ACL graft undergoes extra strain when it hasn’t fully healed yet.

So, in order to effectively build up that strength percentage, you’ll go through an exercise program with steady workout progressions. As you work through the program, you’ll progress from partial squatting to full squatting, and you’ll even be able to perform single-leg exercises like lunges and step-ups. Performing these exercises on one leg will ultimately challenge you to control your leg position, which is otherwise referred to as alignment control. If you lack alignment control, your leg is likely to rotate or collapse inward towards your midline (and that will put your ACL under extra tension, which you definitely don’t want).

Additionally, this second phase will also work on improving your proprioception, which, in a nutshell, is your awareness of your body’s position and movement. Basically, your brain and body are in constant communication with each other to adjust your balance and stability based on where you are in space.

Ultimately, restoring proprioception (specifically in the surgical leg) is essential for returning to running, since you’re basically jumping from one leg to the next the entire time. As you run, your body needs to adjust its stability within hundredths to tenths of a second to produce the power necessary to propel yourself forward. If you aren’t able to use your leg muscles to re-stabilize your body, all of your ligaments — including the ACL — will have to take on extra tension that is detrimental to the healing process.

Your training in Phase 2 will improve your proprioception through simple tasks like balancing on one leg, and you’ll likely progress to more complex tasks as well. An example includes standing on an unstable pad or ball with your eyes closed while reciting the alphabet backwards (which honestly doesn’t even sound super easy without reconstructive surgery).

And that’s the gist of Phase 2 — making sure your leg is strong and stable enough to prepare for the next training transition.

Phase 3: Relearning Proper Force Absorption

Now comes the third and final phase, which usually starts up somewhere between 12-16 weeks after your surgery. (But, just like before, you want to be 100% sure that you’ve met all the proper criteria of Phase 2 before progressing into phase 3.)

At this point in your rehab, the ACL graft has finally healed enough to properly handle the forces of ballistic activities, like light jumping or running. And yes, this is finally the phase where you can (gradually) get back to running!

The transition into this third phase focuses on teaching your muscles how to actively absorb impact during activity. This is why it’s so important that you’ve addressed all the previous training beforehand, otherwise weak muscles or lack of alignment control could place excessive forces on your still-vulnerable ACL.

On top of that, you’ll also continue improving the strength and proprioception of your surgical leg. The primary goal here is to get it back to an equal level of strength and stability as your non-injured leg. Since ballistic activities constantly place higher loading forces on the body, it’s imperative that your leg is well-prepared to take on the repeated impacts of running.

As you begin this phase, you’ll likely start by practicing how to land a small jump on both legs, followed by a progression into repeated jumps on both legs. From there, you’ll move on to landing a small jump on one leg, followed by small repeated hops on one leg. Remember: running is essentially just a series of small jumps from one leg to the other, so these jumping exercises are meant to prepare and assess your leg muscles for that repetition.

Once you’re able to demonstrate sufficient, active control in both hopping and landing, you’re just about ready to ease back into the running world!

How to Safely Start Running Again

Alright, here’s the part you’ve been waiting for: how to actually get back to running.

Returning to any sport after an injury can feel a bit daunting, but rest assured — now that you’ve gone through all the necessary training, you can ease safely back into your activity.

But before we review what that looks like, there’s a bit of fine print to read.

While there’s a lot of extensive research out there on how to get back to running, it’s much easier said than done. We know, we know: you did some thorough rehabilitation, and you promise you’ll take it easy once you start running again. And while you probably do intend to take it slow, if you start to run on your own, it’s still ridiculously easy to overdo it right away.

And here’s why: even with all that pre-running rehab, most people are still extremely stiff in their operative leg, and this places extra stress on your bones, cartilage, and knee (which is still in the process of healing at this point). This stiffness is likely to induce poor running mechanics, which will only increase tension on your ACL graft and its support structures. Even if you start out easy, you’ll be at risk for increased swelling and long-term damage, both of which reduce your ability to progress.

Of course, this isn’t to say that it’s impossible to run again; it’s just not the best time to try and DIY your recovery. An ACL rupture is a complex injury that requires expertise to navigate a proper return to running — and this is where a specialist will become your best resource.

Specialists and physical therapists can create excellent return-to-running protocols based on hard data and your specific rehabilitation journey. These protocols are typically built as custom progressions that can take you from running 1 minute at a time to running 2-3 consecutive miles (or more, depending on what your end goal is).

That being said, even though your ACL is capable of some running at this point, it isn’t necessarily working at full or optimal capacity just yet. So, it’ll still be a bit before you can get back to training.

These custom programs are all about getting you to practice running without hitting any extra setbacks. It’s less of an official return to running than it is a return to practicing running, which is a necessary distinction and a vital step for your healing journey.

As you progress through your return-to-running program, it’s imperative to receive feedback from your physical therapist on how to improve your running mechanics to make sure your knee isn’t under too much stress. Understanding your biomechanics is a big part of furthering your healing process and preventing reinjury.

Plus, with all this feedback, a good physical therapist, and lots and lots of practice, you’ll likely be back to running those 2-3 miles within 6-8 weeks of starting your running program. (Maybe not the speediest of recoveries, but certainly thorough and well-informed!) Once you’re through those last couple of months, you can finally start easing back into running with a training focus (e.g., increased mileage, endurance, pace, etc.).

Final Thoughts

And there you have it. Getting back to running after ACL surgery is as easy as 1, 2, 3 — phases, that is. (Okay, maybe it isn’t easy, but at least the progression is sort of spelled out for you.)

On average, this whole process often takes around 5-6 months after your surgery, but your timeline isn’t an accurate representation of your progress. It’s beyond okay (and normal) to take even longer to confidently get back to safe running. Ultimately, your goal is to complete all the tasks of your progression to make sure you’re effectively healing and improving. Being thorough is the name of the game.

So when your doctor gives you the go-ahead to start running again at that 3-month marker, just remember: they aren’t necessarily wrong, but know to take it with a grain of salt. Seeking guidance from a highly skilled physical therapist is key to effective recovery, a safe return to running, and the ability to run well for years to come.

Thank you for this information. I had ACL replacement in June ’22 and was thinking I was ready to start jogging again now but im feeling some pain and am associating it with needing to better build up the muscles further.

I had an ACL operation on April 22 and I can only start comfortably running with zero to minor pain for 5km after 11 months. I tried running around after 6 months after operation and there is still pain after 3km and need to start walking and dreaded running again. It definitely takes time to go back to almost normal.