Soccer is one of the most played, watched, and loved sports in the world.

Along with being incredibly popular, it also ranks near, if not at, the top of sports with the greatest risk of Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tears for female athletes.

You’ve likely heard of a family member, friend, or child of a friend who has torn their ACL. The news is often accompanied with a “ouch” and grimace face. We’ve all seen professional athletes limp off the field and ride a cart to the locker room after a gruesome hit to the knee or a rogue twist during a cutting movement.

What Is an ACL Injury?

The ACL can be injured in a number of ways, classified in grades. These injuries range from stretching and partial tears to full tears and tibial avulsions. When discussing ACL injuries, literature is commonly referring to Grade 3 injuries, or full ACL tears.

What Is the ACL?

The anterior cruciate ligament is one of four ligaments that protect the knee. A ligament connects bone to bone, is a non-contractile structure, and is the last order of joint stability when the muscular system fails.

The ACL connects the femur to the tibia. It provides stability to the knee by resisting forward motion of the tibia on the femur and by resisting rotational forces.

The other major ligament is the posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments get their name from the Latin “cruciate,” meaning cross, since they literally cross over each other inside the knee joint.

How Do ACL Tears Happen?

A ligament will tear under excessive loading, particularly at end range positions, and usually with rapid accelerations. The ACL is particularly prone to rotational stress.

Surprisingly to most, more ACL tears occur due to non-contact mechanisms versus those when the knee is hit. Approximately 60-70% of ACL tears are non-contact injuries. This means that about 2/3 of ACL tears happen due to preventable biomechanical movement errors.

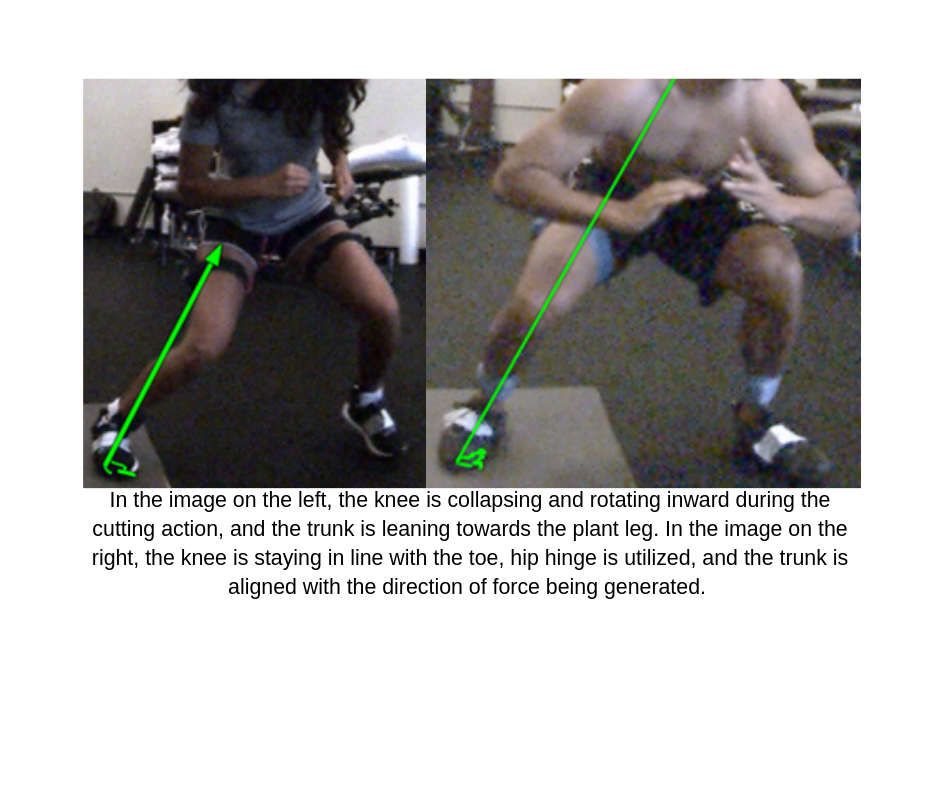

Certain movement patterns have been linked to a higher risk of suffering an ACL tear. These include:

- inward rotation of the knee (internal rotation)

- inward collapse of the knee (adduction)

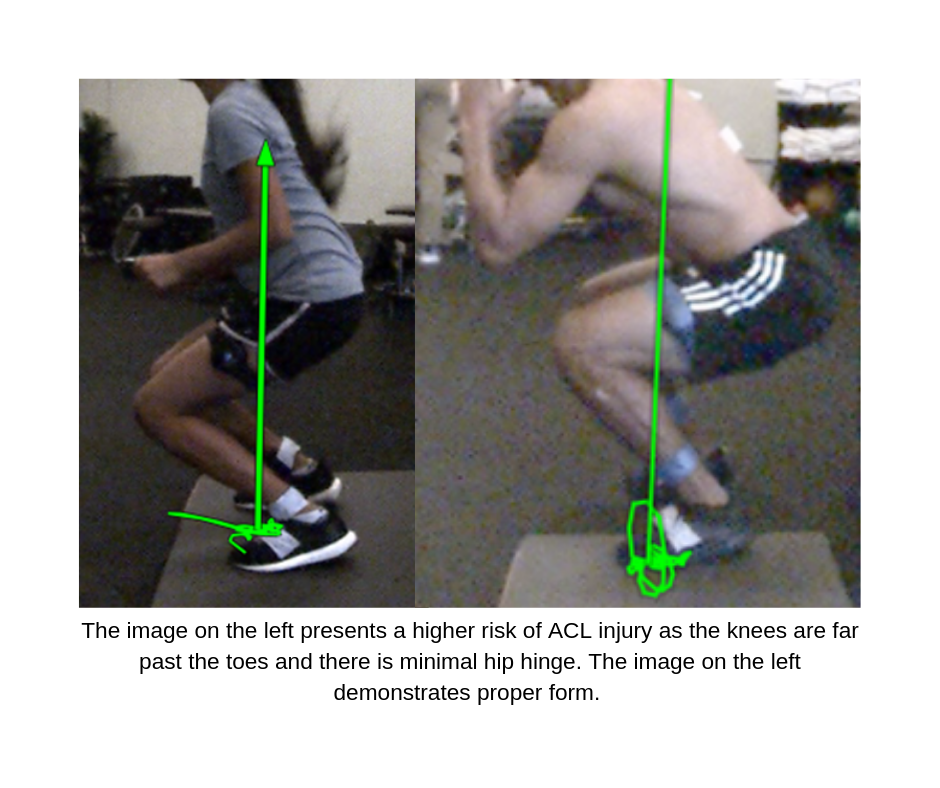

- lack of knee and hip bend with jumping, landing, or change of direction

- trunk lean towards the plant leg

- upright trunk posture with jumping, landing, or agility

These patterns are where preventative programs can have the largest impact. Correcting form errors offers a huge opportunity to reduce the frequency of ACL tears among athletes, but we’ll get to that a bit later.

While some factors are biomechanic, not all are. Some additional factors associated with ACL tears include:

- Female sex

- Poor gluteal strength

- Poor quadriceps strength

- Poor quadriceps to hamstring strength ratio

- Poor core strength

- Larger Q angle

Can You Play Sports After an ACL Injury?

An ACL injury can be career ending for professional athletes and greatly affect a youth athlete’s collegiate prospects. It’s been estimated that after ACL reconstruction surgery, only 55% of athletes return to full competitive play! That means that half of all athletes having ACL surgery won’t return to top performance.

This is an alarming statistic, and one that shouldn’t be taken lightly by athletes, parents, or rehab professionals. As a whole, rehab professionals (physical therapists, athletic trainers) have done a poor job returning athletes back to competition. Return to play after ACL injury is multifactorial, complex, and not an exact science; however, there are essential components that should be included in all rehab plans.

Preventing ACL injury is equally elusive. Although there is no “gold standard” for preventing ACL injury, there are well-known programs that significantly decrease injury risk. The sad truth is that despite growing evidence of their effectiveness, few teams and coaches implement these programs on a regular basis.

Why Are ACL Injuries So Common in Soccer?

Women’s soccer, men’s football, and women’s basketball are often cited as the sports with the highest risk for ACL injury. Football you might expect, but soccer and volleyball often surprise people. Given the biomechanical indicators discussed above, when you break down the movement patterns in soccer, it makes more sense than you might expect.

Movement-Based Risk Factors for ACL Injury

Soccer involves a substantial amount of cardiovascular aerobic endurance interspersed with many quick bouts of anaerobic sprinting. During a soccer match, athletes will average 6-9 miles of running! Plus, players repeat high-intensity bouts of sprinting and cutting every 4-6 seconds.

It also involves an open field of play with highly variable movement patterns and rapid adjustments in body position, direction of running, and kicking actions. Additionally, due to the open field, soccer athletes will often be at full sprint when they make a cutting movement towards center field to shoot or find an open passing lane. Since there is no decrease in running speed, significant workload is placed on the knee for stability.

There are also many instances of close quarters play in soccer where the ball is quickly passed from one player to another causing a defender to rapidly adjust course. These frequent, fast, change-of-direction plays increase the level of fatigue at the quadriceps and hips resulting in greater injury risk at the knee.

Another proposed theory for the higher rate of ACL injury in soccer is due to a lack of strength and plyometric training in youth athletes. Unlike football athletes who start in the weight room as adolescents, soccer athletes often don’t begin a regimented strength and conditioning program until high school or academy league play. Even then, strength and conditioning programs are seen as an adjunct to play rather than an essential component of injury prevention and performance enhancement.

Why Are Females Soccer Players More at Risk for ACL Injury?

Women are 3x more likely to tear their ACL than their male counterparts!

Anatomically, females have been found to have greater anterior tibial laxity, meaning there is more available movement between the shin bone and thigh bone, which increases ACL injury risk.

Despite anatomical differences, research has shown that neuromuscular factors are the largest contributor to the gender difference in ACL tears (though some environmental and hormonal factors also exist).This disparity can manifest in several ways.

ACL tears occur during deceleration, cutting, changing direction, and landing actions in sports. In females, there appears to be a decrease in the stiffening of the knee prior to sports based actions. The quadriceps and hamstring are delayed in firing patterns creating a brief moment of laxity that leaves the knee at risk of injury.

When comparing female athletes to male athletes, females take significantly longer to generate maximal hamstring torque during isokinetic testing. Basically, the rate of contraction, or how fast an athlete is able to contract muscular tissues during sports actions, is delayed in females compared to males.

When studies have observed differences in jumping and landing patterns of males versus females, they have noted that females are more likely to use a knee-dominant movement pattern and males are more likely to use a hip-dominant movement pattern.

A knee-dominant movement pattern demonstrates an upright trunk, limited hip and knee flexion, greater ankle dorsiflexion, and decreased gluteal muscular activation. A hip-dominant movement pattern maintains greater hip and knee flexion, a hip hinged posture, greater gluteal muscle activation, and improved knee control.

Since the ACL is most susceptible to rotational forces, it is imperative to have optimal gluteus maximus and gluteus medius activation and strength to control rotational stability of the knee. The quadriceps and hamstrings control knee stability forward and backward while the gluteal musculature controls knee stability in sideways and rotational directions.

Strength programs are even less common in women’s soccer than they are in men’s soccer. Until recently, they were almost entirely lacking, meaning that female players were neglecting developing strength and control through the gluteal muscles and increasing neuromuscular response, putting them at higher risk for an ACL injury.

What Are ACL Injury Prevention Programs, and Do They Actually Work?

Following ACL injury, approximately 80% of athletes will undergo reconstructive surgery. Rehabilitation following ACL surgery can take anywhere from 6 months-1.5 years. With such a large amount of playing time lost, especially during crucial athletic prospect years such as junior year of high school or college, preventing ACL injury has become a prime focus for FIFA and other soccer organizations.

What are ACL Prevention Programs?

Currently, there is no “gold standard” ACL prevention program. There are many different ideologies and training methods; however, agreement does exist that neuromuscular, agility, and single leg stability drills are essential.

For soccer athletes, programs should include deceleration, cutting, jumping, landing, single leg landing, strength training, and plyometric elements. Programs should include specific movement feedback to improve motor learning. Feedback should be both visual (video) and verbal, starting with frequent feedback and decreasing cues as time goes on. Variable sport-specific practice should be incorporated as the plan progresses.

Soccer warm-up programs have been particularly effective at decreasing ACL injury risk; however, their adoption and integration by coaches has been unfortunately minimal.

The FIFA 11+ Warm-up Program

One of the most studied warm-up programs is the FIFA 11+. The warm-up program takes approximately 20 minutes to complete and consists of 15 progressive exercises divided into three sections:

Section 1: Slow running and active stretching

Section 2: Core and leg stability, balance, plyometrics, agility

Section 3: Fast running and cutting motions

According to meta-analysis studies, consistent application of the FIFA 11+ decreases overall injury rate by 35-39%! In a survey of approximately 1200 soccer coaches, only 50% even knew the FIFA program existed! This lack of awareness must factor into the overall injury rate.

Since soccer athletes need to warm-up for sport play anyway, why not use a program with a proven track record of injury reduction?

How ACL Injury Prevention Programs Work

The success of the FIFA 11+ comes from utilizing neuromuscular control drills that challenge single leg stability, agility, power development, and plyometrics. By using this program on a consistent basis, soccer athletes build sport specific motor patterns that they can draw upon in game play.

Other programs, like the PEP program, follow similar training methods. The key takeaway is that some form of neuromuscular “priming” or systemic warm-up is essential for reducing injury risk. Static stretching, jogging, and skill practice alone isn’t sufficient motor priming to reduce injury risk.

At the beginning of the season, screening tests like a step down, drop jump, and triple hop can be easily used to flag at-risk athletes and to track their injury risk over time. The Y-balance test is another tool with a normative database that can help catch those athletes who need additional training.

For at-risk athletes, those with previous injury, or those who demonstrate more biomechanical movement errors, a more comprehensive strength, conditioning, and neuromuscular control program is recommended. A sports-specific physical therapist or athletic trainer is ideal for this level of training.

The Future of ACL Injury Prevention

Women’s soccer participation is rapidly growing which means ACL injury prevention is more essential to protect youth and collegiate athletes. It isn’t just females who would benefit from more specific and effective ACL injury prevention programs. Although males don’t tear their ACL at the rate of females, the injury still plagues youth, collegiate, and professional male soccer players.

It is essential to develop science-based programs to limit ACL injury risk. Warm-up programs like the FIFA 11+, which have already proven successful in reducing injury risk, need to be utilized by soccer coaches on a consistent basis. This starts with mandating these programs be performed before practice and games as league standards. If we know it works, why aren’t we using it?

From high school onward, pre-season, mid-season, and end of season injury screening tests should be routinely tracked to ensure at-risk athletes get the care and attention they need. Not only will this help reduce injuries but the neuromuscular programs themselves will build foundational movements essential to performance.

Strength and conditioning programs need to be mandated for soccer athletes. This includes quadriceps, gluteal, calf, hamstring, and core strengthening. Soccer specific drills for agility and plyometrics should also be a focus.

Finally, education for players, parents, and coaches will ensure the entire “team” is on the same page and focused on the BEST drills and programs to decrease injury risk.