If you’ve ever looked for guidance on running form, chances are, you’ve probably heard of a little something called overstriding. It’s one of the most common and notorious running issues out there… yet very few runners fully understand what it is and what it means for their running gait.

Countless magazines and blogs discuss the evils of overstriding, often using diagrams of stick figures with large, red icons to emphasize what not to do. It’is certainly an effective way to get the point across; the visual representation is a great reminder that you shouldn’t be reaching your leg out as far as possible while you’re running.

But there’s only so much you can gain from a stick figure and knowing what not to do.

Most people will know that overstriding is bad, but there are still plenty of questions left hanging in the air — like how far out should your foot land? At what point does a stride become an overstride?

The answers all lie within the biomechanics!

As much as we all love a good stick figure diagram, you deserve hard, data-based evidence; so let’s dive into defining overstride by using some actual running data (from real-life runners!) and learn how to eliminate overstride for your best possible running form and efficiency.

Who’s ready??

What is Overstride?

Before we head into all the nuances, let’s get the basics out of the way first.

An overstride, in its most basic definition, occurs when your front leg extends too far in front of your body whenever you take a step.

Pretty straightforward, right?

Well, yes, but we aren’t ones to settle for the basics! There’s obviously much more to it than just having strides that are too long (otherwise it wouldn’t warrant an article as lengthy as this one!). This simple definition provides a general understanding of the issue, but it leaves a lot to be desired when it comes to feeling confident in being able to identify and address it within your own running form.

Thankfully, advanced technology allows us to measure real-time metrics in optimal (and suboptimal) running gaits, providing us with 2 data-backed methods for pinpointing overstride.

Data Point #1: The Angle of Your Tibia

If you’re thinking that sounds extremely specific, that’s the whole point!

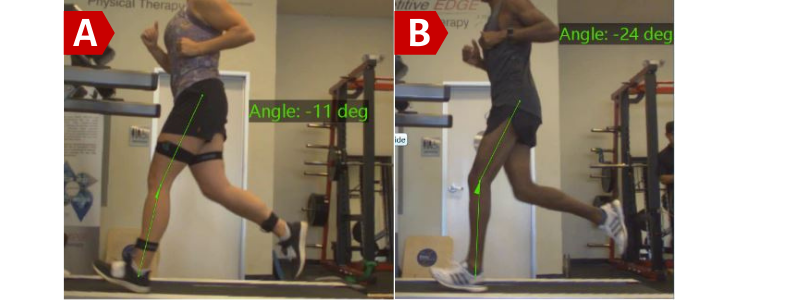

The angle of your tibia (otherwise known as your shin bone) can be a major indicator of whether or not your leading leg is extending too far out in front of you. The key here, however, is to focus specifically on the angle during initial contact.

Initial contact refers to the moment when your leading foot first touches the ground; it’s the first step of the stance phase in the running gait cycle, and consequently, the ideal phase to measure the angle of your shin bone to assess overstride. (The only caveat is that this isn’t something you can easily observe with the naked eye; you’ll have to record your gait in slow motion from the side view to get the most accurate analysis.)

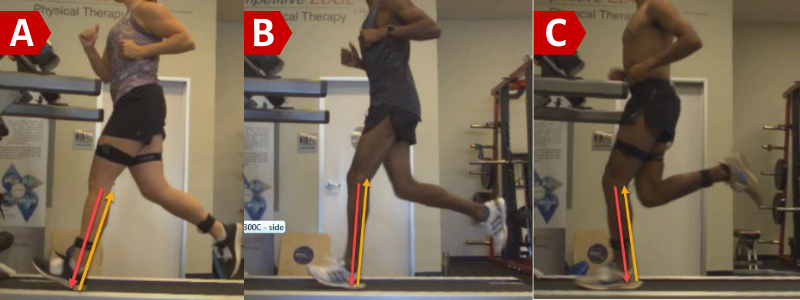

Below are a few examples of runners with different tibia angles; the colored arrows indicate the nature of the tibias’ angles. (Image A: backwards-angled tibia; Image B: vertical tibia; Image C: forward-angled tibia.)

Of these examples, the Image A would be considered an overstride, whereas Images B and C have tibia angles that occur with proper, efficient running form.

The difference boils down to one of the most basic physics principles: every action has an equal and opposite reaction. (We know, we know — you didn’t come here for a physics lesson, but just hear us out.)

The acceleration and direction of your tibia will determine how ground reaction forces impact your body. With an overstride, your body weight will be pressing forward and away from your body (down the angle of your shin), meaning that the responding impact forces will end up pushing backwards against you, ultimately resulting in a braking force on impact.

With the forces working in the opposite direction of your running, you’ll experience slower running speed and will require significantly more energy in order to keep up your usual pace. Not to mention the increased braking and landing forces will also increase risk of injury, especially the longer you leave it unaddressed.

According to numerous studies, any backwards degree of the tibia is considered an overstride. (That’s why many specialists will label an overstride as minimal, moderate, or significant dependent on the degree of the tibia’s backwards incline.)

Data Point #2: The Distance Between Your Foot and Pelvis

For this method, you’ll also be focusing on that point of initial contact (how convenient!), but this time, we’re shifting our focus from degrees to distance.

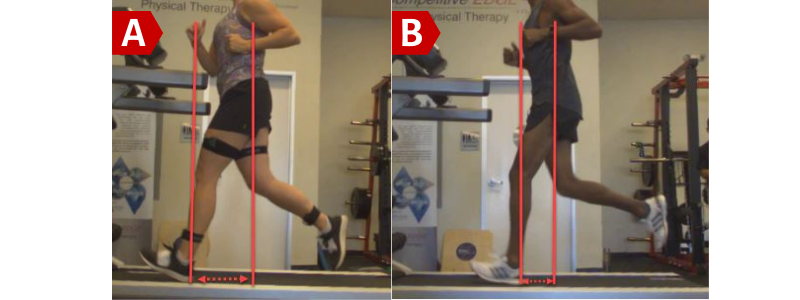

More specifically, you’re measuring the distance between where your foot lands and where the center of your pelvis is. (Horizontally; we aren’t talking about running a tape measure up your leg!) Here are a couple more examples to help you visualize what that looks like:

In these images, we’ve placed vertical markers to indicate the runners’ initial points of contact as well as the center points of their hips. As you can observe, Image A shows a larger distance between the runner’s heel and their hips, indicating overstride, whereas Image B shows a point of initial contact placed closer underneath the center of the body.

It may not be the most intuitive correlation, but having your foot land underneath your hips is key to ensuring safe and effective shock absorption. Keeping your foot under your center of gravity requires you to bend at the knee and hip, a motion that recruits imperative muscle groups for running (including your quads, glutes, and calves). When these muscles are properly activated, they’re primed for absorbing the impact forces — meaning they can better store energy and “reuse” it in your push-off for a more powerful and efficient forward motion.

In short, keeping your initial point of contact underneath your hips will not only eliminate your overstride, but it will ultimately improve your running efficiency and power (all the while protecting your back, hips, and knees!).

Big gains from some small changes, right?

In Image A you can observe that the runner’s knee is only slightly bent (and without our technology, you might even think the knee was straight). Conversely, Image B shows a much more noticeable angle at the knee, presenting more than double the degrees compared to the runner with overstride.

Similar to the tibial angle example, any initial point of contact that lands outside of your center of gravity will technically qualify as an overstride. Specialists will use the “minimal,” “moderate,” and “significant” qualifiers here, as well.

Common Causes of Overstride

Phew! That was a lot just for identifying the issue, huh? (We told you it runs way deeper than simply stepping too far ahead!)

But don’t take off your thinking cap just yet, fellow runner — there’s more to divulge.

Now that you have a better understanding of how nuanced a simple stride can be, it goes without saying that there are countless factors that can impact your form and cause overstride…

But it’d be a bit too overwhelming to review EVERYTHING in one post. So instead, let’s dissect three of the most common causes for overstride and how they impact your running performance in the grand scheme of things.

Decreased Cadence

This is probably the biggest, most common issue correlated to overstride: low cadence.

If you aren’t already familiar, cadence measures how many steps you take per minute; it’s a relatively simple metric to track, but it plays a key role in optimal running mechanics.

Most studies demonstrate that a cadence around 172-180 is the most ideal for proper running form, and anything that drops below 172 may increase your risk of running with overstride. (That’s not a guaranteed connection, but if left unchecked, a low cadence is likely to lead to overstriding.) You can think of it this way: taking fewer steps to cover the same amount of mileage means you’ll end up compensating for distance by elongating your stride.

However, when you run with a faster cadence, your gait cycle has to turn over at a faster rate — meaning your feet don’t have as much time to extend out in front of you. This will ultimately pull your initial contact landing point back towards your center of gravity, allowing you to take more steps that carry you forward faster and more efficiently.

Now, you might be wondering — if increasing your cadence brings your foot in, doesn’t that mean it’s shortening your overall stride?

Technically, yes, but beneficially. Remember: while overstriding seems like a good short-term solution for gaining maximal ground with every step, it’s called overstride for a reason. Start out by eliminating overstride, thus naturally improving your form; then, as you continue to hone your form and biomechanics, you’ll eventually make up that “loss” of distance by learning how to increase your stride length behind your body, rather than in front of it. (But that’s a topic for another blog!)

Insufficient Trunk Lean

The second most common variable that often leads to overstride is the amount of trunk lean you maintain while running.

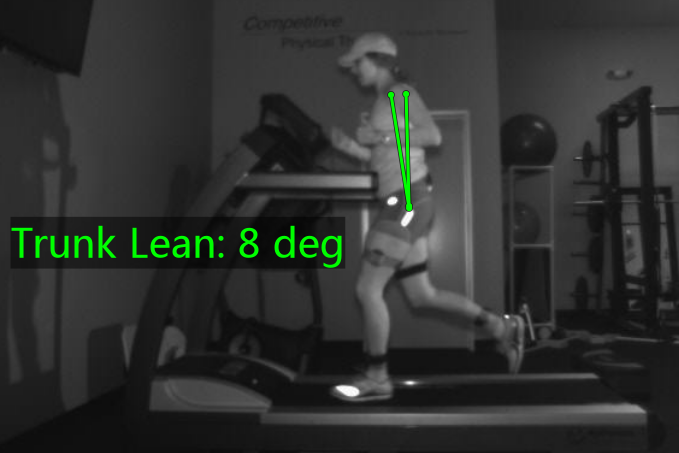

Trunk lean refers to the forward angle of your torso whenever it leans forward from an upright position. (The key word here is “lean”; you don’t want your torso to experience any flexing or bending! Your spine should still be straight, just slightly tilted forward.)

Ideally, you should be running with a small forward trunk lean, somewhere around 8-10 degrees forward and hinging at the hip. It might sound meticulous, but sufficient trunk lean allows for proper bending mechanics at your hip; this creates the avenue for proper muscle activation and power generation in your gluteal muscles.

And, as previously mentioned, the activation of your glutes is a vital aspect for efficient shock absorption, so you want to be sure you’re giving your hips as much opportunity as you can to ensure they’re at peak functionality!

Unfortunately, many runners end up running with an upright trunk, and that leads to a myriad of biomechanical deficiencies… Including overstride.

Another interesting connection, isn’t it? Most people probably wouldn’t correlate their trunk posture to how far they step, but here we are.

When you run with an upright trunk, it essentially provides more room for your hamstring muscles (the muscles that make up the back of your thighs) to stretch forward when you bring your leading leg up to your center of gravity. It’s a pretty subtle and overlooked aspect of running muscle mechanics, but that extra wiggle room gives your body a whole lot of leeway to extend much further out than it needs to.

Running with just those few degrees of trunk lean is enough to restrict the length of your hamstring muscles. This prevents your leading leg from moving too far forward, thus keeping it under your center of gravity.

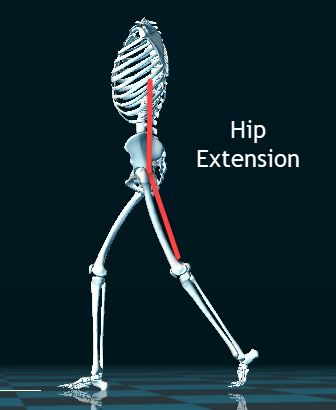

Decreased Hip Extension

Next up on the list is poor mobility during hip extension. (Or, in less fancy terms, when you feel tightness or restriction in the muscles at the front of your hip.)

These muscles are known as your hip flexors, and they’re the ones responsible for the range of motion at your hip joints. This includes the ability to extend your leg behind your body to get that optimal push-off as you move into your next step.

But with tight hip flexors, that becomes a whole other story.

Limited mobility at the hips will restrict the amount of distance your leg can travel behind the body, shortening your stride. In the context of your running gait, that may not seem all that bad, but when you zoom out to the bigger picture, a shorter stride for every step will put a pretty large dent in your usual running speed. (And since running time is one of the simplest tangible metrics for assessing running performance, most of us don’t love seeing it change for the worse.)

What ends up happening is that runners will typically feel the decrease in speed and overcompensate by reaching forward in their steps to gain stride length — and that’s where the dreaded overstride begins to manifest.

Your stride length is sort of like a sliding range: the less length you have in front of you, the more you’ll need behind you (and vice versa). With minimal stride length ahead of you, your body will have to extend the stride further behind you to maintain sufficient strides. But, if you overstride, your body is fooled into thinking you’ve hit a good stride length, so it neglects to focus on achieving that extra length behind you.

Foot Strike and Overstride

Alright, so this isn’t exactly a cause of overstride so much as a common misconception…

Because overstride is so heavily correlated with that initial point of contact, many people are led to believe that their method of foot strike has an impact on their striding mechanics as well.

Surprisingly, though, that isn’t the case.

Runners, regardless of forefoot, midfoot, or heel striking patterns, can all be susceptible to running with overstride. Granted, a good chunk of heel strike runners exhibit more overstride than forefoot runners, but that’s not a guaranteed correlation.

This is because our heels have more cushion than the rest of the foot, so it’s easy for runners to land hard on their heels while overstriding. It’s also not as natural to land on the balls of our feet when extending our legs further out. So, while heel striking and overstriding are frequently paired together, one does not inherently cause the other.

Rather than adjusting your foot strike, correcting overstride requires a more in-depth, biomechanical approach to adjusting aspects like cadence and trunk lean. Where you land on your foot is far less important than where your foot lands on the ground!

Final Thoughts

And there you have it: a detailed, comprehensive look into all things overstride. (Well, most things.)

Even though the concept behind overstride is simple and may appear easy to identify, there’s plenty of biomechanical nuance between every individual runner. When it comes down to having a thorough analysis of how your overstride presents within your gait, you’ll benefit most from analyzing the side view of your gait right at the point of initial contact.

We know you just read through this beast of an article for the sake of understanding the specifics, but here’s the quick and dirty reference guide on what elements to focus on for correcting overstride:

- Increase cadence to 172 or above (gradually! Check out this guide for more assistance.)

- Adopt a slight forward trunk lean (8-10 degrees)

- Extend your stride behind your body, rather than in front

- Stretch your hip flexors to improve hip range of motion

- Improve your gluteal activation and strength

- Work with a running biomechanics specialist

Keep in mind, though, that having the knowledge of what to address is only the first step; adapting to different biomechanics takes time and diligence in order to correct your form safely. (It’s still 100% doable, just don’t expect it to magically fix itself within a matter of days!)

So lace up your shoes, fellow runner; assess your running form and start making strides in your performance — the RIGHT way!